Conversation With Rubén Torres Llorca

François Vallée

Rubén Torres Llorca was born in Havana in 1957. He graduated from the San Alejandro Art Academy in 1976 and from the Instituto Superior de Arte in 1981. His work has been included in numerous exhibitions and biennials and is part of important private and public international collections.

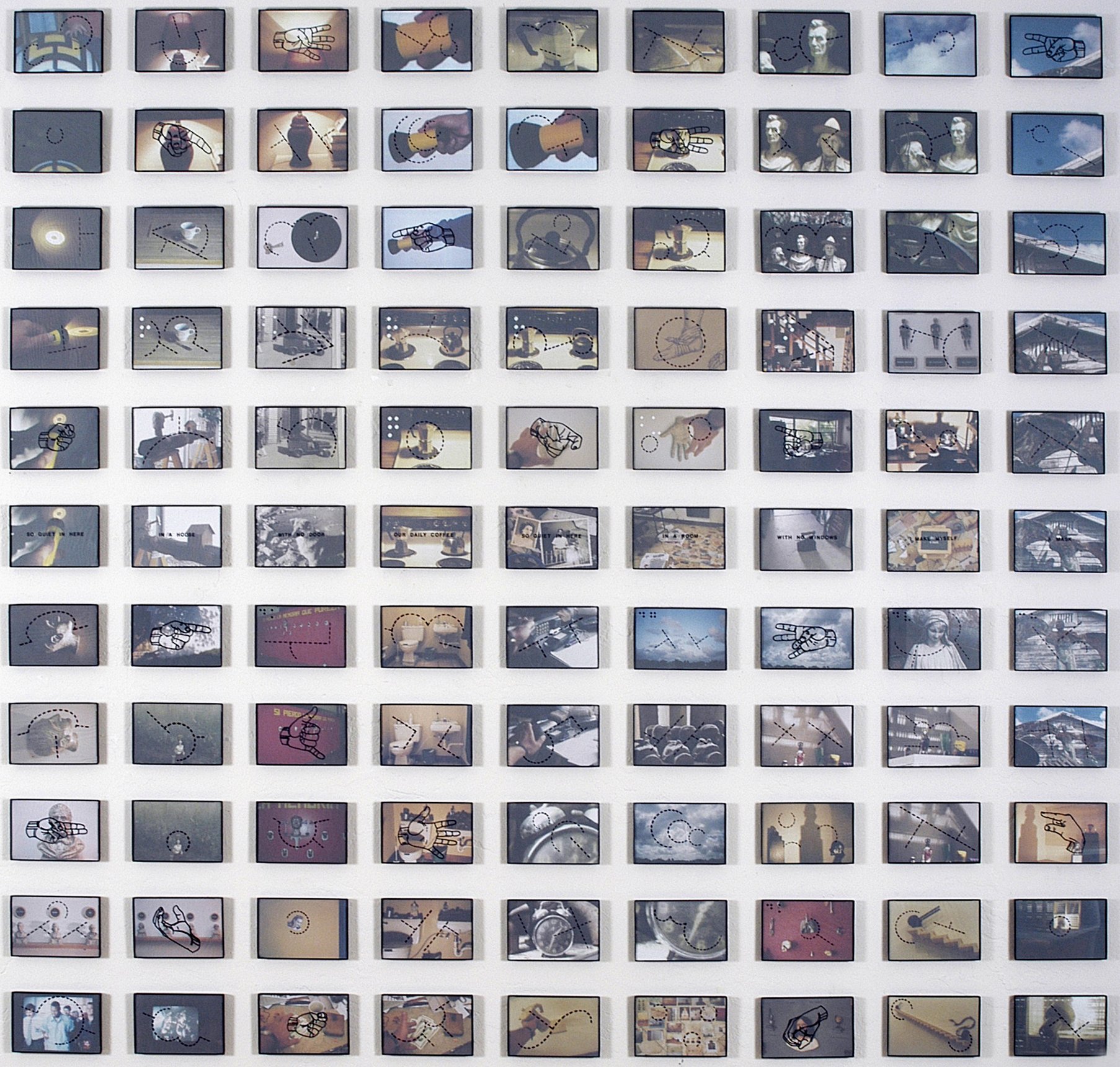

Torres Llorca's work is completely part of a project to "shape" the world, influenced by the artistic avant-garde of the 1920s, but also by the conceptual approach of Magritte or the anti-aesthetic sensibility of Beuys. The protean nature of his work defies any attempt to classify it. His penchant for blurring the boundaries between different artistic media such as painting, drawing, collage, objects, sculpture, installation; its symbolic use of heterogeneous natural materials such as wood, textiles, paper, cloth, clay, rope; his defense of an interdisciplinary between the arts; they imply an implicit questioning of the role that the artist plays today and of the status of the work of art in our society.One of the central axes of his work is the work of memory; manipulating historical and sociological matter in a fictional way, he constitutes a mythical construction enterprise whose origin is the totalitarian culture in which he grew up. Torres Llorca's art is political, in its philosophical sense; it is a manifestation of freedom, it creates the conditions for an experience of liberation, an engine of self-determination. Likewise, he assigns to art the mission of transforming the meaning of language and concepts: he is interested in the conformation of these attempts to express thought as something plastic.The work of Rubén Torres Llorca is a sensitive experience that materializes the energy of thought in order to awaken the viewer's capacities for perception and reflection. He is one of the most emblematic and influential Cuban artists of the last forty years, since he experiments and innovates without ceasing, problematizing, questioning and regenerating the formal and the conceptual. He shares the Nietzschean vision of art as revealer, revealer, deconstructor and interpreter of man, of modern culture and society.Let's start with a self-portrait: tell me about your childhood in Cuba, about your family...

My childhood was horrible, like that of any decent artist. But the possible traumas that are inferred from that horror have been so overcome that I am lazy to answer the question. In part, it will answer itself.What was your first aesthetic emotion? When do you think art became the center of your life?

Evading compulsory military service was what led me to study art. I have never had a great vocation for anything, but since I was a child they came to me with the story that my father was a good painter, that he studied in San Alejandro, etc. My father died at the age of twenty-two, fighting for the Revolution. We never met. It was raised in the Sierra Maestra while my mother was still pregnant. Perhaps, in addition (elementary Dr. Freud), studying painting was an attempt to win my father back. In any case, art has never been the center of my life, rather an alibi that justifies it and nourishes me.What training did you have? How do you value the teaching you received?

With a bit of luck, I had a great teacher in San Alejandro: Antonio Alejo. Learning the craft resources of art is a trial and error. You practice and practice, and if you have the good genes for it, you learn the craft. Which doesn't make you an artist. No one can teach you to be an artist. The essential function of art schools is to teach you a trade and, inadvertently, put you in touch with your generation.How have you evolved as an artist?

I have gone from being an artist, in the romantic and traditional sense of the word, to being an essayist. An essayist who reflects on the art of the past and the present dictatorship of the art market. I have undergone a transition from creator to intellectual.Simplifying a lot, let's say that the plastic arts exhausted their autophagy with the conceptualist movement. Art, as we knew it, disappears and is supplanted by the dictatorship of the art market. In other words, no renowned artist acts without taking market forces into account. These economic forces are marked by a strange new dance of unwritten rules between the intolerance of the right and the inconsistency of liberalism.However, within the peculiar conditions of the timeless bubble and the isolation of Cuban society in the decade from 1979 to 1989, it was possible to be an artist, to be an avant-garde, the old-fashioned way. In this context, metaphorically speaking, it was not only possible, but necessary, to rediscover the wheel.The plastic arts, thanks to the absence of a market and not needing, like other arts, the production of the state, became the main spokesperson for many socio-political and cultural concerns of the Cuban people. These conditions no longer exist in Cuba, where today's artists are fully alert and integrated into the international market. Even the artists who use art with some success as a political weapon do so from the international market. Upon emigrating, and starting my life over in the real world, being an artist quickly became obsolete.Which artists have influenced you and which ones do you still admire?

Undoubtedly, some plastic artists have had a great influence on my work, but more because of their ideas than because of their form. The most notable would be Joseph Beuys, Umberto Peña and Mario García Joya. But my most important influences come from literature, and especially from cinema.How do you judge your generation, the one from the 1980s?

My generation is extraordinary.Perhaps one of the great tragedies of the Revolution is that they educated us without considering that this education would help us think independently of official dogma. The eighties brought a time of détente to Cuba, after all vestiges of intellectual opposition against the Revolution were extinguished in the 70s. In this context of lobotomy that Cuban culture was suffering, the generation of Volume I began to act, ready to reinvent culture, to make revolution within the Revolution.In this landscape where there was practically no other creation than that dictated by the regime, being an artistic vanguard (by comparison), reinventing artistic trends, was natural. Thus, in almost complete ignorance of the past, we dusted off pop art, performance art, conceptual art, etc., and international critics inserted this accident into the post-modern movement.This pause in the repression, this vacillation of the regime, allowed, for a few years, that unlike the artists of Eastern Europe, we were able to generate an authentic and vibrant art. In the late 1980s, and with Perestroika on the horizon, the regime decided we were making too much noise, and old-fashioned censorship resumed. Faced with the impossibility of working on the island, the vast majority of my generation emigrated abroad.How do you value contemporary Cuban art?

The reality is that now I have very little contact with current Cuban art, even that Cuban art that is produced outside of Cuba. Except for the casual or sporadic inclusion in some historical exhibition.Tell me about your creative process.

My works work within the semantic possibility that all certainty is questionable. In them, the words deny the meaning of the images and vice versa. All the problems are verbal.I have a natural curiosity for psychology, psychoanalysis and sociological research. The first step of any project is to know the public that frequents the space that I am going to use. My exhibitions, projects and installations are structured like a film, a novel or an essay. Or small essays within a narrative, trying to maintain maximum verbal economy and visual synthesis. When we visit a traditional plastic arts show, given its iconic nature, it is the viewer who chooses a starting point, based on what first attracts their attention. I try to manipulate the space, building walls, divisions, ordering the works by their content, and not aesthetically. In this way, the viewer is physically forced to read the individual pieces in a certain order, as paragraphs of a whole. This allows me to create a dramatic arc and this dramaturgy provokes a catharsis.A good part of my work is closely linked to my socio-political concerns. I don't claim to be a role model, but, as an intellectual, the only political position that is drinkable to me is to always be in opposition, to create balance, no matter who is in power. All power (left, center and right) is inherently corrupt. All social systems we know of are imperfect.Without those who create friction within systems, there would be no progress. What really attracts me is creating a space for discussion. Any resource, coming from any medium, no matter how bastard, can be used. Literature is as important in my work as any other element. The visual narratives of my works are opposed to literary narratives, with the aim of creating dramatic tension. My imagery tries, within my artisanal limits, to be academic, realistic, and devoid of "style." Something we could see in a book from the forties or in a museum of anthropology and science. Which does not worry anyone and allows a first reading where the viewer feels before something familiar. To this I oppose the text, which generally denies, challenges, and ironizes the image. What Antonin Artaud called "poisoned candy".An important factor in inserting myself (or advertising myself) as a visual artist is the comparatively low investment that is needed to produce a visual object, and therefore, the less dependence I have on a producer. You can make visual arts with garbage and in the middle of the street. At the beginning of my career in Cuba, the only possible producer for all the arts was the State. A book, a concert, a play, a film, were produced, and therefore filtered, according to the interests of power. In capitalism there is a greater space for movement, but equal dependence and possible manipulation of the producer.Do you create without thinking about an audience, be they friends, collectors, gallery owners...?

What is your relationship with the art market?

I try, with extremely modest results. Our level of incidence in the public is minimal when we are outside these circles, but the possibilities of our work being manipulated are greater when we participate in them. I repeat, all power is corrupt; the artist has always been the weakest link in these chains. The art market, economic transactions, totalitarian states, powerful collectors, curators, art dealers, art critics, and other intermediaries have gradually supplanted the cultural hero role of the artist.What relationship do you maintain with the other arts?

I could happily live the rest of my life with the only occupation of enjoying movies, music and literature. The list of my favorite works in these three manifestations would be greater than the space of the interview. The plastic arts, I'm sorry, they don't have any mystery for me.When and why did you decide to go into exile?

When they told me I was going to be a father. I wanted to give my son other possibilities of movement. Capitalism is hideous, but there is more room to evade blows.What remains of Cuba, and of Havana, in your life and in your art?

Universality resides in the individual, the personal, the everyday. In order not to fabricate a pamphlet, honesty with ourselves, accepting who we are, is a crucial part of the artwork.In the countries where I have lived: Cuba, Mexico, Argentina, the United States, in some way my experience has been similar to growing and maturing, to that love-estrangement relationship that one establishes with parents upon reaching adulthood. You love them, but you can't help but see their flaws and limitations.Framing an artistic production within a regional framework is a double-edged sword. It may have its ideological values or cultural or anthropological rescue. But more frequently it is also an instrument of the market and the circles of power, which has several objectives, among them: to sell a folkloric article, or to mark the production of certain groups of artists as a second-hand product, and to diminish its value of change, be it economic, cultural or ideological. But more frequently it is also an instrument of the market and the circles of power, which has several objectives, among them: to sell a folkloric article, or to mark the production of certain groups of artists as a second-hand product, and to diminish its value of change, be it economic, cultural or ideological. No one questions the nationality or origin of artists who move from the metropolis, such as Damien Hirst or Matthew Barney. Both show their identity in that tremendous display of economic power that permeates their respective productions.Who we are will manifest itself regardless of our intentions. In my particular case, to give just one example, the way I build my works is directly influenced by the structuralist way in which Afro-Cuban religions display their altars. To create culture you need a cultural past, and in the Cuba where I grew up, the closest thing to modern art was a Santeria altar, and above all the organic attitude towards the surrounding reality with which practitioners build these altars. This is not obvious in a large part of my production of the last two decades, from the moment when, leaving Cuba and changing the context, it was no longer necessary for me to use the imagery or the content of these religions, only their strategies. aesthetic.

Conversación con Rubén Torres Llorca

François Vallée

Rubén Torres Llorca nació en La Habana en 1957. Se graduó en la Academia de Arte de San Alejandro en 1976 y en el Instituto Superior de Arte en 1981. Su obra ha sido incluida en numerosas exposiciones y bienales y forma parte de importantes colecciones privadas y públicas. La obra de Torres Llorca se inscribe por completo en un proyecto de “puesta en forma” del mundo, influenciado por las vanguardias artísticas de los años 1920, pero también por el enfoque conceptual de Magritte o la sensibilidad anti-estética de Beuys. El carácter proteiforme de su obra desafía cualquier intento de clasificación. Su inclinación por desdibujar las fronteras entre los distintos medios artísticos como la pintura, el dibujo, el collage, el objeto, la escultura, la instalación; su uso simbólico de materiales naturales heterogéneos como la madera, el textil, el papel, la tela, la arcilla, la cuerda; su defensa de una interdisciplinaridad entre las artes; implican un cuestionamiento implícito del papel que desempeña el artista hoy en día y del estatuto de la obra de arte en nuestra sociedad. Uno de los ejes centrales de su obra es el del trabajo de la memoria; manipulando la materia histórica y sociológica en un modo ficticio, constituye una empresa de construcción mítica cuyo origen es la cultura totalitaria en la cual se crió. El arte de Torres Llorca es político, en su sentido filosófico; es una manifestación de la libertad, crea las condiciones de una experiencia de la liberación, un motor de autodeterminación. Asimismo asigna al arte la misión de transformar la significación del lenguaje y los conceptos: le interesa la conformación de estas tentativas de la expresión del pensamiento como algo plástico.La obra de Rubén Torres Llorca es una experiencia sensible que materializa la energía del pensamiento a fin de despertar en el espectador capacidades de percepción y de reflexión. Es uno de los artistas cubanos más emblemáticos e influyentes de los últimos cuarenta años, ya que experimenta e innova sin cesar, problematizando, cuestionando y regenerando lo formal y lo conceptual. Comparte la visión nietzscheana del arte como desvelador, desocultador, deconstructor e intérprete del hombre, de la cultura y la sociedad modernas. Empecemos por un autorretrato: háblame de tu infancia en Cuba, de tu familia…

Mi infancia fue horrible, como la de cualquier artista decente. Pero los posibles traumas que de ese horror se infiere han sido tan superados que me da flojera contestar la pregunta. En parte, se va a contestar sola. ¿Cuál fue tu primera emoción estética? ¿Cuándo piensas que el arte se convirtió en el centro de tu vida?

Evadir el servicio militar obligatorio fue lo que me llevó a estudiar arte. Nunca he tenido gran vocación por nada, pero desde niño me venían con el cuento de que mi padre fue un buen pintor, que estudió en San Alejandro, etc. Mi padre murió a los veintidós años, luchando por la Revolución. Nunca nos conocimos. Se alzó en la Sierra Maestra estando mi madre aún embarazada. Quizás, además (elemental Dr. Freud), estudiar pintura fue un intento de recuperar a mi padre.En cualquier caso, el arte nunca ha sido el centro de mi vida, más bien una coartada que la justifica y me alimenta. ¿Qué formación tuviste? ¿Cómo valoras la enseñanza que recibiste?

Con un poco de suerte, tuve un gran maestro en San Alejandro: Antonio Alejo. Aprender los recursos artesanales del arte es un trial and error. Practicas y practicas, y si tienes buenos genes para ello, aprendes la artesanía. Lo cual no te hace un artista. Nadie te puede enseñar a ser artista. La función esencial de las escuelas de arte es enseñarte un oficio e, involuntariamente, ponerte en contacto con tu generación. ¿Cómo has evolucionado como artista?

Yo he pasado de ser un artista, en el sentido romántico y tradicional de la palabra, a ser un ensayista. Un ensayista que reflexiona sobre el arte del pasado y la presente dictadura del mercado del arte. He sufrido una transición de creador a intelectual. Simplificando mucho, digamos que las artes plásticas agotaron su autofagia con el movimiento conceptualista. El arte, tal y como lo conocíamos, desaparece y es suplantado por la dictadura del mercado del arte. Es decir, ya ningún artista de notoriedad actúa sin tener presente las fuerzas del mercado. Estas fuerzas económicas son demarcadas por una nueva y extraña danza de reglas no escritas entre la intolerancia de la derecha y la inconsecuencia del liberalismo.Sin embargo, dentro de las condiciones peculiares de la burbuja atemporal y el aislamiento de la sociedad cubana en la década de 1979 a 1989, era posible ser artista, ser vanguardia, a la vieja usanza.En ese contexto, metafóricamente hablando, era no solo posible, sino necesario, redescubrir la rueda. Las artes plásticas, gracias a la ausencia de mercado y a no necesitar, como otras artes, la producción del estado, devino el principal vocero de muchas preocupaciones socio-políticas y culturales del pueblo cubano. Estas condiciones no existen más en Cuba, donde los artistas de hoy están completamente alertas e integrados al mercado internacional. Incluso los artistas que usan el arte con algún éxito como arma política, lo hacen desde el mercado internacional.Al emigrar, y recomenzar mi vida en el mundo real, ser un artista se convirtió rápidamente en algo obsoleto. ¿Qué artistas te han influenciado y a cuáles sigues admirando?

Sin duda, algunos artistas plásticos han tenido una gran influencia en mi trabajo, pero más por sus ideas que por su forma. Los más notables serían Joseph Beuys, Umberto Peña y Mario García Joya. Pero mis influencias más importantes vienen de la literatura, y sobre todo del cine. ¿Cómo juzgas a tu generación, la de los años 1980?

Mi generación es extraordinaria.Quizás una de las grandes tragedias de la Revolución, es que nos educaron sin considerar que esa educación nos ayudaría a pensar con independencia del dogma oficial. Los años ochenta trajeron a Cuba una época de distensión, después de que todo vestigio de oposición intelectual contra la Revolución fue apagado en los 70. En este contexto de lobotomía que sufría la cultura cubana, empezó a actuar la generación de Volumen I, lista a reinventar la cultura, a hacer revolución dentro de la Revolución. En este paisaje donde prácticamente no existía otra creación que aquella dictada por el régimen, ser vanguardia artística (por comparación), re-inventar las tendencias artísticas, era natural. Así, en casi completa ignorancia del pasado, desempolvamos el arte pop, el performance, el arte conceptual, etc., y la crítica internacional insertó este accidente dentro del movimiento post-moderno. Esta pausa en la represión, esta vacilación del régimen, permitió, por unos años, que a diferencia de los artistas de Europa del Este, fuéramos capaces de generar un arte auténtico y vibrante. Al final de los ochenta, y con la Perestroika en el horizonte, el régimen decidió que estábamos haciendo demasiado ruido, y la censura a la antigua se reanudó. Ante la imposibilidad de trabajar en la isla, la gran mayoría de mi generación emigró al extranjero.¿Cómo valoras el arte cubano contemporáneo?

La realidad es que ahora tengo muy poco contacto con el arte cubano actual, incluso ese arte cubano que se produce fuera de Cuba. A no ser por la casual o esporádica inclusión en alguna exposición histórica. Háblame de tu proceso de creación.Mis obras funcionan dentro de la posibilidad semántica de que toda certeza es cuestionable. En ellas, las palabras niegan el significado de las imágenes y viceversa. Todos los problemas son verbales.Tengo una curiosidad natural por la psicología, el psicoanálisis y la investigación sociológica. El primer paso de todo proyecto es conocer al público que frecuenta el espacio que voy a utilizar. Mis exposiciones, proyectos e instalaciones, están estructuradas como un filme, una novela o un ensayo. O pequeños ensayos dentro de una narrativa, tratando de mantener la máxima economía verbal y síntesis visual. Cuando visitamos un show tradicional de artes plásticas, dado su carácter icónico, es el espectador el que escoge un punto de partida, basado en aquello que primero atrae su atención. Yo intento manipular el espacio, construyendo paredes, divisiones, ordenando las obras por su contenido, y no estéticamente. De esta manera, el espectador está forzado, físicamente, a leer las piezas individuales en un determinado orden, como párrafos de un todo. Esto me permite crear un arco dramático y esta dramaturgia provoca una catarsis. Una buena parte de mi trabajo está estrechamente ligado a mis inquietudes socio-políticas. No pretendo que sea un modelo a seguir, pero, como intelectual, la única posición política que me resulta potable es estar siempre en la oposición, crear balance, no importa quién esté en el poder. Todo poder (izquierda, centro y derecha) es intrínsecamente corrupto. Todos los sistemas sociales que conocemos son imperfectos. Sin esos que crean fricción dentro de los sistemas, no existiría el progreso. Lo que realmente me atrae es propiciar un espacio de discusión.Cualquier recurso, proveniente de cualquier medio, no importa lo bastardo que sea, puede ser utilizado.La literatura es tan importante en mi obra como cualquier otro elemento. Las narraciones visuales de mis obras se oponen a las narraciones literarias, con el objetivo de crear una tensión dramática. Mi imaginería trata, dentro de mis límites artesanales, de ser académica, realista y exenta de un "estilo". Algo que podríamos ver en un libro de los años cuarenta o en un museo de antropología y ciencias. Lo cual no inquieta a nadie y permite una primera lectura donde el espectador se siente ante algo familiar. A esto le opongo el texto, que generalmente niega, desafía, e ironiza la imagen. Lo que Antonin Artaud llamaba "el caramelo envenenado".Un factor importante en insertarme (o anunciarme) como artista visual, es la reducida inversión que, comparativamente, se necesita para producir un objeto visual, y por tanto, la menor dependencia que tengo de un productor. Se puede hacer artes visuales con basura y en medio de la calle. Al inicio de mi carrera en Cuba, el único productor posible para todas las artes era el Estado. Un libro, un concierto, una obra de teatro, una película, eran producidos, y por tanto filtrados, de acuerdo a los intereses del poder. En el capitalismo existe un mayor espacio de movimiento, pero igual dependencia y posible manipulación del productor.¿Creas sin pensar en un público, sean amigos, coleccionistas, galeristas…?

¿Cuál es tu relación con el mercado del arte?

Lo intento, con resultados extremadamente modestos. Nuestro nivel de incidencia en el público es mínimo cuando estamos fuera de estos círculos, pero las posibilidades de que nuestro trabajo sea manipulado son mayores cuando participamos en ellos. Repito, todo poder es corrupto; el artista ha sido siempre el eslabón más débil de estas cadenas. El mercado del arte, las transacciones económicas, los estados totalitarios, los poderosos coleccionistas, curadores, art dealers, críticos de arte, y otros intermediarios, han suplantado paulatinamente el papel de héroe cultural del artista. ¿Qué relación mantienes con las otras artes?

Yo podría vivir alegremente el resto de mi vida con la única ocupación de disfrutar del cine, la música y la literatura. La lista de mis obras favoritas en estas tres manifestaciones sería mayor que el espacio de la entrevista. Las artes plásticas, lo siento, no tienen ningún misterio para mí. ¿Cuándo y por qué decidiste exiliarte?

Cuando me anunciaron que sería padre. Quería darle a mi hijo otras posibilidades de movimiento. El capitalismo es horroroso, pero hay más espacio para evadir los golpes. ¿Qué queda de Cuba, y de La Habana, en tu vida y en tu arte?

La universalidad reside en lo individual, lo personal, lo cotidiano. En orden de no fabricar un panfleto, la honestidad con nosotros mismos, aceptar quiénes somos, es parte crucial de la obra de arte. En los países donde he vivido: Cuba, México, Argentina, Estados Unidos, de alguna manera mi experiencia ha sido similar a la de crecer y madurar, a esa relación de amor-distanciamiento que uno establece con los padres al llegar a la adultez. Uno los quiere, pero no puede dejar de ver sus defectos y limitaciones. Enmarcar una producción artística dentro de un marco regional es un arma de doble filo. Puede tener sus valores ideológicos o de rescate cultural o antropológico. Pero con mayor frecuencia también es un instrumento del mercado y los círculos de poder, que tiene varios objetivos, entre ellos: vender un artículo folclórico, o marcar la producción de determinados grupos de artistas como un producto de segunda mano, y disminuir su valor de cambio, ya sea económico, cultural o ideológico. Nadie cuestiona la nacionalidad o procedencia de artistas que se mueven desde las metrópolis, como por ejemplo Damien Hirst o Matthew Barney. Ambos muestran su identidad en ese apoteósico despliegue de poder económico que permea sus respectivas producciones. Quienes somos se va a manifestar con independencia de nuestras intenciones. En mi caso particular, por poner solo un ejemplo, la manera en que construyo mis obras está directamente influenciada por la manera estructuralista en que despliegan sus altares las religiones afrocubanas. Para crear cultura se necesita un pasado cultural, y en la Cuba donde yo crecí, lo más cercano al arte moderno era un altar de santería, y sobre todo la actitud orgánica con la realidad circundante con que los practicantes construyen estos altares. Esto no es obvio en una gran parte de mi producción de las últimas dos décadas, desde el momento en que, al salir de Cuba y cambiar el contexto, ya no me fue necesario utilizar la imaginería o el contenido de estas religiones, solo sus estrategias estéticas.Links

Smithsonian Archives of American Art

Oral History Interview, Audio, With Ruben Torres Llorca, January 1998

Spanish